A review of Revolutionary Road (2008, directed by Sam Mendes )

One of the most effective criticisms that can be made of people who choose to live an alternative lifestyle is that it is (in the terms of this movie) whimsical or flighty. An alternative lifestyle is presented as a set of artifices that may make complete sense when initially constructed but can’t replace the foundation of how one has to live. Whether one’s life leads to riches or rags, one must make sensible choices about how one goes about the journey. Your journey is still here, in this world.

A bohemian, whether called a hipster, a radical, or a slacker scoffs at this definition of sensibility. It’s a big joke that generation after generation laughs at, slapping knees and each others backs until such time as they pause to catch a breathe, finding themselves as the object of the laughter. This big joke is closely examined by its participants only in a series of desperate attempts to find enough people who share enough values and aesthetic sensibilities so that an urban, childless, bohemian life isn’t meaningless. Every one else just sees this as the activity of childhood, of children, of people who aren’t taking certain biological or socio-economic aspects of life seriously, fantasy creatures who do not live in this world. For everyone else there will be offspring careers, and taking care of elderly parents. Whatever alternative lifestyles have to offer they aren’t, generally, meaningful responses to hard questions around retirement, child rearing, health care, et al.

The Revolutionary Hill Estates had not been designed to accommodate a tragedy. Even at night, as if on purpose, the development held no looming shadows and no gaunt silhouettes. It was invincibly cheerful, a toy-land of white and pastel houses whose bright, uncurtained windows winked blandly through a dappling of green and yellow leaves

–Revolutionary Road (the novel)

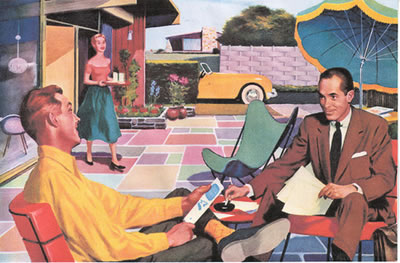

Revolutionary Road (the address of DeCaprio and Winslet in the movie) is the perfect place to raise a family and participate in the all the benefits of regular, mid twentieth century middle class life. Friends who don’t interest you. Neighbors you can barely stand. No one who ever wants to talk about life outside of the mundane. Beach trips, dinner parties and an occasional trip to a nightclub extend suburban work life outside of the work day. This routine, and even homogeneity itself, is the only way that white collar workers can possibly maintain their sanity while doing something that they hate.

Why is this? Why is routine and mundanity a necessity for office workers mental health? A crass interpretation would be that when you are doing something horrible, something that you can’t stand, then you have to shut down your critical impulses, as they are unnecessary facilities that just get in the way of the activity you have decided upon. Damn the consequences!

“No one forgets the truth; they just get better at lying”

–Revolutionary Road (the novel)

I haven’t read the novel that the movie is based on but I have to believe that it was a friendly response to it. Every quote I have found from the novel reflects the emotional moment that I found in the movie. Shiny happy reality wrapped around the sadness of choices that have moved beyond your ability to make them.

The casting of DeCaprio and Winslet was excellent in this regard. The two of them made their careers (and, I’m sure could have retired on the proceeds) as the romantic leads of the movie Titanic, the story of an enormous ship whose slow motion CGI dismantling far exceeded any actor’s ability to… exist. In this way the two movies share a common sensibility. Suburbia is the Titanic, born of hubris and monotony, preparing to hit a future that will sink it. But as actors these two have grown a great deal since Cameron’s heavy handed ministrations.

In the first movie Winslet was barely there,she was, more or less, the invisible half of a “great romance” which is the body-without-organs of cinema life. To her great credit Winslet went from being a Shakespearean actor, to Titanic, to indie films where she has spent most of the past decade (RR probably would be considered an indie film in the denatured terms that apply in the film-making industry). Her role in Revolutionary Road is the opposite of the Titanic role. Winslet is at the height of her power as an actor and as someone who is willing to make the fully aware and awake break from this world. For the story of Revolution Road, the myth of another path is called Paris; but almost anywhere could be the outside of patterned misery, of a job that they hate, of a life that holds no joy. Her arc in the movie includes putting her body on the line in the name of Paris (or at the very least getting out of suburban purgatory).

DeCaprio is a difficult actor to like. For over a decade he has been (especially early in his career) called the next Marlon Brando but he has yet to rise nearly to the level of a Brando or a Deniro. He is more likely to be spoken of as an actor in the same breathe as a Ben Affleck or Colin Farrel (not Clooney, Pitt or Damon). He is totally competent (even if it is hard to look at his face without worrying about how many bathroom breaks his director is giving him) but his risk taking (as an actor) seems… safe. DeCaprio’s role in Revolutionary Road is, again, competent, as he plays a character who seems prepared to leave behind a life of pedantic misery… until he isn’t.

Whereas the relationship in Titanic was all honeymoon (love and bliss and shit), the marriage in Revolutionary Road is the reality of what happens when the romance leads to children and ten years later you look up are realize you are fucking miserable–not just with the life you lead in this world, which is self-evident, but with the person you are living it with. What does falling out of love feel like? Most of us have this experience but it doesn’t make the transition to the plastic arts. We know that love looks like inhumanly beautiful people making kissy face but what does falling out look like? It doesn’t look like a dramatic fight with dishes and yelling since that still seems to lead to the kissing and the staying together. It looks like something else.

A ballet perhaps, where the feints and pirouettes replace action and honesty; where communication resembles a light slit experiment, exposing the incongruity between two types of behaviors, life and routine, passion and obligation, love and hate, the present and the myth. And as with most incongruity our skills aren’t suited for transition well. We do it poorly. We move from one thing to another with great stubbornness and inelegance. There is no ballet to the breakup. Things get messy and unclear.

The list is thousands long

People who decided it wasn’t for them

Did they really make that decision?

Conditioning runs deep in the U.S.A.

Teenage rebellion is just fine as long as you stop once you turn eighteen

Thousands of punks turned to society’s tools

There is something in their eyes

You can tell they sold out

-Filth The List

I am enough of a realist to understand the material reasons that counterculture/Bohemia (of which my particular post-hardcore, anti-authoritarian scene is but one of many) represents a chapter of most people’s lives (and not even a major one). I am also enough of a troubled dreamer to resent this and my resentment is not simple. On the one hand I don’t hold it against those passing through but on the other I sincerely wish it weren’t the case. I wish that there were enough here in this scene, whether it was material or spiritual, to keep everyone who finds my particular solutions ([anti]political, cultural, aesthetic), to be solutions for life.

The phenomena being reflected on is that individuals are not bound to each other tightly. They can experience the entire oeuvre of a decade-old band in an afternoon. They get resources from their class and Wikipedia explains their interconnections to the world. The critique of ideology has been fantastic for late anarchists in that it has allowed us not to get trapped by pastoralism or workerism, but it has also created a context where nothing that we can do to change the world is good enough to rise to even that level of description. Our critique of the incompleteness of our own activity has assured most of us that our activity is not good enough. It only makes sense that we abandon critique as incomplete. This autodigestion–coupled with the material force of this worlds pressures–is enough to convince the most die-hard Boheme to add their name to The List. But there is no list and no more home.