Fate, Love and Revolution in Mawaru Penguindrum

“If people were all locked into trains headed toward predictable destinations, who would ever give rise to those unpredictable and unforeseen events we call revolutions?”

Fredy Perlman, Letters of Insurgents

Mawaru Penguindrum is set in a world without revolutions. Kunihiko Ikuhara’s second original anime following 1997’s Revolutionary Girl Utena, Penguindrum is a meditation on the nature of such a world – a frozen world, where no-one sees any hope of change. The unspoken context for Penguindrum is a void of revolutionary hope, a hope which disappeared with the end of the radical movements of the 1960s. This is a world full of lonely, alienated individuals clinging to their own strategies for survival, often at the expense of others. All these people have is inertia and the unbearable weight of social judgment to conform, a suffocating peace punctuated by occasional bursts of violence. Those who can’t or won’t conform are pulled towards people who say they can change the world, people who give them hope and direction in life. This was Japan in 1995, the backdrop for Penguindrum, where the Aum Shinrikyo cult launched a sarin attack in the name of apocalyptic war on the Tokyo subway system. This is the world in which we continue to live.

In this void wander our protagonists, the Takakura siblings, consisting of the brothers Shouma and Kanba, and their sister Himari. They are some of those who cannot conform to society, for society will not let them. They have the unfortunate distinction of being the children of some of the people who perpetrated this alternate world’s version of the Tokyo sarin attacks. When their parents abscond, society puts the blame on the children instead, who now live as pariahs. They are all unwanted or abandoned, none related by blood, a found family in which each clings to the other as a way to survive in this world. The tragedy of their family is the tragedy of society writ small – they too see no hope of changing their situation. That is, until something miraculous happens.

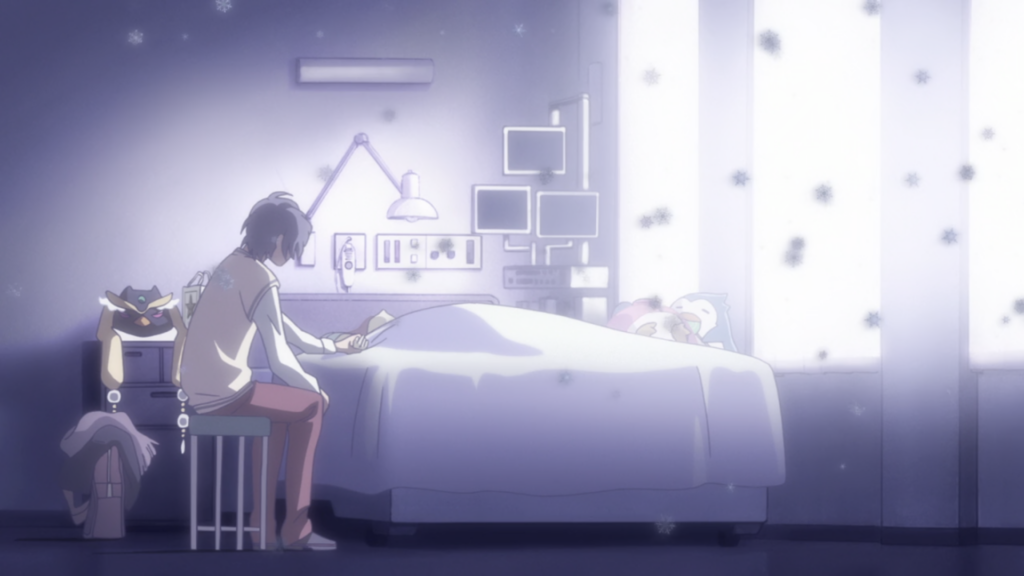

This miracle begins in horror, as the brothers watch Himari collapse during a family outing. Alone in the hospital room with her corpse laying between them, the brothers can only see this horrible turn of events as fate having finally punished them for the crimes of their parents. Fate is the defining logic of their world. It gives them a way to rationalize Himari’s chronic illness as well as their ostracization by society. It also appears in the ubiquitous images of trains – characters are constantly getting on and off them, and the show is peppered with scene transitions of subway billboards and blaring alarms that warn of their coming and going. It’s a fitting image for a predictable world where everything seems inevitable, orderly, and without hope of anything unexpected happening. Yet no sooner is Himari dead than the unexpected occurs – she seems to come back to life! This is conditional, however. The brothers must find the mysterious Penguindrum, or death will claim her once again.

Is Himari alive or not? Are miracles possible? Could we actually have a revolution? Ikuhara comes down firmly on the side of maybe. In this show, revolutions happen but nothing changes. Miracles are fragile and easily crushed but their legacies endure. Himari lives and dies and lives again. The wild ride Ikuhara takes the siblings for will showcase his own skepticism of big-R Revolutions and the Society they struggle against. Yet there is also hope – a hope that this unchanging world can be overcome, or at least survived, through revolutionizing our relationships with one another.

But perhaps it’s too early to be talking of hope – after all, Ikuhara’s just getting started. Throughout the early part of the show, we watch the brothers hustling onto subway trains, alternately bossed around and insulted by Himari’s doppelganger, the Princess of the Crystal. The subway is like the quest itself, reducing life and its myriad possibilities to tracks headed in a single direction – follow the signs and reach your desired destination, follow the rules and reach a good ending. The Princess is demanding of the brothers, yes, yet rules to follow and goals set before them mean they’ve been presented with something they’ve been denied thus far: the possibility of escaping the fate that’s been assigned to them since they were children. Underlying the bombastic rock-and-roll score that greets us when the Takakuras enter the realm of the Princess is a dirge, an oppressive weight bearing down on the family: the visceral reality of Himari lying dead in the hospital bed, the septic spareness of the hospital room. It’s the sound of something fragile being crushed even as it struggles to survive. In their minds the jig’s up, and now the bittersweet interlude they’ve been in since the disappearance of their parents has finally ended. Even without conceding to fate, we can share in the horror and grief of the brothers, as well as their excitement when Himari seems to return to them.

Their newfound hope is fragile. How could it be otherwise? At the heart of this simplified version of the universe is the hard reality that Himari is still on the verge of death, and they’re attempting the impossible.

Life Against Death

The bulk of Penguindrum sees the Takakuras and their fellow travelers groping around in the dark, trying to find hope and meaning in a world where there seems very little of either. In their desperation, they find themselves shuffled onto trains, or actively seeking out conductors that give them some direction in life. This existential drama is heady stuff, but Ikuhara grounds it in the actual event of the Aum Shinrikyo subway attack. Cults are a perfect fit for this kind of train thinking – members of Aum found a conductor for themselves in the form of a spiritual leader who would eventually order them to wage an apocalyptic war with the rest of the world.

To Ikuhara, the void of hopelessness in which people latch onto (or are latched onto by) cult leaders is a political void. According to him, those who carried out the bombing were alienated from the vapid youth culture which followed the collapse of social movements in Japan in the 60s: “Young people in any time period are carrying some kind of drama, the same went for me. Thinking back on it now, I was at risk too. An age without easily understood movements is actually more dangerous.” Here Ikuhara is contrasting the general social unrest and sometimes violent actions carried out by members of mass movements to the anti-social violence of desperate people who turn to obscure sects such as Aum in their rebellion against society.

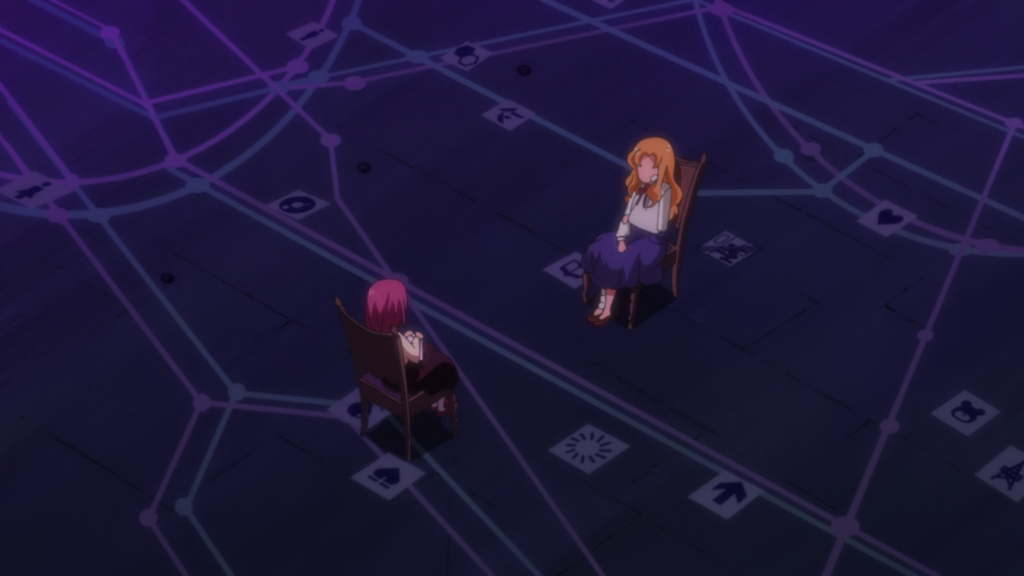

This question of hopelessness and how we respond to it is at the heart of Penguindrum, and Ikuhara produces two answers: the apocalyptic death cult led by Sanetoshi, and the fragile hope of the not-so-ordinary high school girl Oginome Momoka. Both of these characters are revolutionaries, both oppose the world as it exists, but the differences between them couldn’t be more stark.

For both the Takakuras and the cult that he leads, Sanetoshi is a savior whose arrival offers hope for changing the world at a time when all hope seems lost. Waltzing into the story halfway through the show with all the affected ease of any would-be master of society, he arrives to collect the Takakuras as sheep who have strayed from his flock since the disappearance of their parents. Hope for the Takakuras means reviving Himari, who is again on her deathbed, with the Princess’s powers waning. For the cult, it means the destruction of the society they’re at war with. Like many demagogues, from mystical to Marxist, Sanetoshi is constantly decrying the horrors of society. His rhetoric is seductive because there’s truth to it. After all, they’re living in a world in which falling outside the social body means (social) death, and unwanted children are literally ground up in a giant machine called the Child Broiler, to be reformed into faceless, anonymous masses. His cult, like the real-life Aum, offers not just belonging and purpose, but survival.

Yet for all his hatred of society, it’s clear that Sanetoshi remains a part of it. Take his revival of Himari – she’s barely sitting up in the hospital bed when he presents Kanba with the bill1. “How much do you want,” asks Kanba. “As much as you think she’s worth,” replies Sanetoshi. We haven’t left the world of debt and limited resources, with Himari still on a life support of sorts with increasingly mounting bills. Kanba works for the cult, which sends him money for their living expenses in exchange for planting bombs around the city. Society insists that the Takakuras must suffer for the sins of their parents while Sanetoshi insists that they must take up the cause of their parents. There is no new freedom here, but as Msr. Dupont says, only “the harsh victory of the law of our ancestors over the dimension of our becoming” (Nihilist Communism).

Ikuhara’s lament, that people in contemporary society turn to things like cults and sporadic anti-social violence in the absence of social movements, is a familiar one among many anarchists. Yet he isn’t exactly coming to bat for old leftist movements, either. He ties the movements of the 60s to Sanetoshi through a shared sense of extreme justice: “The belief these movements had in an absurd sense of justice gave them them power to fight the adults. Listening to the words of the people who committed the ‘95 incident, each and every one had that sense of being correct, so fastidious they’d make you ill.” In his view, justice is an easy answer to the complex problem of society. Neither the movements nor Sanetoshi can deal with complexity or ambiguity, instead favoring the tunnel-vision of big revolutions and exacting punishment upon their enemies. Incidentally, this way of seeing the world also makes it a lot easier to kill people who don’t fit your idea of being right. No wonder trains are so attractive to these people, given how fast the details of everything outside the windows pass by when you’re speeding from point A to point B.

Oginome Momoka’s version of revolution gets into all the messy details Sanetoshi wants to avoid. In a world where big-R revolution seems to have failed, her revolution is disrupting the kind of fated thinking haunting the minds of socially isolated people like the Takakuras. Where the Sanetoshis of the world see useful idiots and targets of revenge, her response to alienation is to extend her hand in friendship. Momoka says to these people that, despite what society says, they matter to her simply because they exist. This value isn’t predicated on whether they are useful to her, she loves them for them regardless of how much time they spend farting around on the subway. Solidarity fills the void that drives Ikuhara’s troubled youth into the arms of self-avowed saviors.

This kind of love is rare, it’s the kind of love we usually expect from our families, define that how you wish. Families take many forms for Ikuhara, including the traditional, mom-dad-and-the-kids family, found families such as the Takakuras, and cults. None of these are inherently good – in fact, as we see time and time again, they’re often pretty bad. Parents dominate children. We’re expected to stand by people even when they hurt us. People use each other and call it love. And even the best of families may do terrible things to those who fall outside of it, in the name of survival. This last part is shown through the Takakura parents, who are both loving and dedicated parents and killers of random people on the Tokyo subway. Their violence is motivated by exactly this love, this commitment to protect their children from the society that seeks to grind them up.

In Penguindrum, just like in life, being in a family can be fucking hard. Both of the people Momoka befriends experience a painful reality lurking underneath a familial love they took to be self evident and unquestionable. Familial love can take on the train logic of revolutions, offering comfort and predictability but sacrificing choice, creativity, and freedom. The Takakuras really get put through the wringer on this one – at some point the bottom falls out of their relationships, and they’re left asking, what’s the point of all this anyway? What’s keeping us together, especially when we’re making each other so unhappy? This is the same rock that many anarchist attempts at community have been dashed upon. Having no assumed basis for our relationships, it’s easy to bolt when things get hard, and leaving complicated and/or bad relationships is often cast as the right thing to do.

With Momoka we can say that this lack of assumed relations offers the possibility for a love that revolutionizes the lives of the people involved. This possibility is represented as a liminal space in which a subway has been flattened, a stark visual contrast with Sanetoshi’s trains. There is no forward or backward at this point, but free movement through a space no longer defined by signage, conductors, or momentum in any particular direction. This is exactly the kind of space for the “unpredictable and unforeseen” to happen. This lack of a natural order allows her to transgress social boundaries and build more meaningful relationships. There are limits to Momoka’s transgression, however. She doesn’t inhabit this space of pure possibility all the time. And even when she’s in that space, there’s still a give-and-take when possibility becomes reality. Bringing a hamster back to life gives her a cut, and disrupting an abusive relationship puts her in the hospital. In the hospital we see her bandaged hand covering the hand of the friend she’s saved, a girl whose own hand was once bandaged due to her father’s abuse. There is no pie in the sky waiting at the end of a revolutionary struggle here, but an endless process of becoming.

Yet even with all of the possibility offered by Momoka’s approach to the world, what results isn’t always that great. Society creeps in over time. Years after her death, the friends whose lives she intervened in will form a kind of cult of Momoka, miserable people obsessed with her legacy, with lives bearing very little resemblance to their founder. Momoka’s devotees will stand in the way of our protagonists, insisting, like Sanetoshi, that the Takakuras take the blame for the actions of their parents. We can mourn the fleeting presence of revolutionaries such as Momoka, people who lives fiercely and disappear all too quickly, but the greater tragedy is that, at the end of the day, she ends up on the same pedestal as Sanetoshi.

Life after Death

Ikuhara appears troubled by this sad fate of revolutionary life, returning to it again and again in his work. In Utena the titular character ditches her oppressive world on a motorcycle, in Yuri Kuma Arashi Kureha and Ginko are forced out with a hail of bullets. Revolution is fragile and fleeting. It cannot coexist with the world it opposes – it finds a way out or it’s destroyed in the process. If any fragment of hope remains, it lives on in fairy tales, stories of the past, and the dreams of children, thus why so much of Penguindrum is spent watching the characters fight over Momoka’s middle school diary. Throughout this show, we see how the past can capture us just as much as it inspires us, obliging us to reproduce what’s come before. We think we’re heading somewhere new, but it turns out we never left the train we were on in the first place.

If the old social movements are gone and their spiritual heirs – the mystery cults and revolutionary leaders of the world – can only offer a mix of suicidal false hope and cynical manipulation of their believers, what’s left? For Ikuhara, the answer lies in our continuous attempts to revolutionize our relationships with one another. There’s a kind of bittersweet hopefulness here. As Ikuhara reiterates in the Guidebook, this show was inspired by the idea that no death is in vain.And indeed, at the end of the show, Momoka wins her battle with Sanetoshi. The Takakuras as well as her friends have embraced the kind of familial love that she embodied. She is gone, but her ideas live on.

Neither of our revolutionaries get the last word in Penguindrum. Ikuhara reserves this for the living, not the dead. The Takakuras commit to living with each other as a family without illusions. Shouma, Kanba, and Himari have learned to live together as Takakuras, the family name that’s brought them so much trouble, because in Ikuhara’s view, living is kind of painful to begin with. Accepting the burden of family means accepting the messiness of the world we are born into. That is to say, Shouma’s initial strategy for survival in this world, to lament his undeserved pain and attempt to disown it, doesn’t cut it. But neither does Kanba’s doubling down and embracing that pain through his work with the cult. It’s this kind of deep existential stuff that revolutionaries are contending with, the biggest example in this show being the fact that we need each other to live in this world. Alienation here isn’t just a product of capitalist social relations but a fundamental part of the human experience, portrayed at one point as Kanba and Shouma reaching out to one another through literal prison cells that divide them. What finally bridges this gap, with Himari as their guide, is their love for each other and their willingness to shoulder that pain together. The pain of living is inevitable, as are all the thorns to be found among the relationships with the people we love and need most. The best we can do, it seems, is to do those relationships better than society expects us to.

Or is it? Despite the posi nihilism of this ending – similar in energy to Everything Everywhere All at Once, where, after so much drama, nothing changes but the protagonist’s mentality towards her mundane existence – it seems that our director can’t make up his mind. No sooner have the Takakuras revived their embattled family from the brink of dissolution then they are torn apart again. We actually do get a revolution, but one that’s very different from Aum Shinrikyo or the old leftist parties. Revolution here is an act of love that changes the world but doesn’t hold it hostage. After the family reconciles, the brothers, like Momoka before them, sacrifice themselves to exorcise the ghosts of the past – the legacy of their parents, the ghosts of Sanetoshi as well as Momoka. The end result is ambiguous. The world has been reformed into something less painful, but also a bit less alive, less colorful. The world our found family built for themselves to shelter from society’s judgment is gone, the riotous color pallet we were greeted with in the opening episode now toned down. Himari is alive, still sick, but stable. But the brothers are gone, and with them any memory of the drama that’s unfolded over the past twenty-some episodes.

And yet, traces of this other world remain. We see two young boys who look strikingly like our disappeared protagonists walk by the house. These mysterious characters are discussing how there are no endings, that death is only the beginning of another journey, and that they can go anywhere they want. And in a corner of Himari’s bedroom sits a riotously pink stuffed bear, a memento from the previous world, along with a note from her brothers telling her they love her. She sees the bear, brushes her hair back in a gesture we’ve seen time and time again through the series, a gesture towards continuity amid so much change, and cries at the memory of another lifetime.

This continuity is important, because it tells us that life continues. The fact we’ve also seen these same boys at the beginning of the series emphasizes the non-linearity of the story we’ve just been told. Despite all of the explosive and sometimes surreal drama, especially in the lead-up to the end, the world ends up looking kind of the same. Ikuhara revels in these kinds of broken circles, and so it often is for anarchists when we attempt radical change. Even in the minutia of our everyday lives there are rarely clean breaks with what came before. What are we then to make of Himari’s tears? Is this the birth of a new cult rooted in loss, or have we finally escaped fate? We are given no answers. Such is the nature of spaces without tracks or signage to tell us what’s ahead. But we get a clue from the new scar on Himari’s forehead. Momoka’s body also bore the marks of change from saving others. This is what she showed Yuri to convince her that she could change the world, telling her, what’s one more bandage if it means I can save your life? We don’t regret all the scars we bear. So I can’t help but think that, at the end of Penguindrum, when Himari tells her absent brothers “I will always love you,” this love, and the scars that came with it, may be evidence of life and not death.

A Postscript on Penguins

Now if much of this seems like it’s all doom and gloom, well, it’s not quite. Penguindrum is actually quite a funny show, and the director invites us to laugh at fate as much as he shows how it tortures people. A big part of this, as the show’s name might suggest, has to do with penguins. The Takakuras are accompanied throughout by cartoonish penguins whose screen presence is mostly defined by ridiculous antics when they’re not waddling around making weird noises. Viewers are treated to a series of very loud farts from Shouma’s penguin during a very serious, painful argument he’s having. Kanba’s penguin is prone to taking upskirt photos. Attempts by the brothers to use these penguins to carry out their mission are invitations to disaster. These fumbling penguins offer an amusing contrast to our highly-stressed, highly-motivated brothers. In the guidebook for the series, Ikuhara celebrates the “anarchy” (interviewer’s word) of the penguins as things that are “basically useless, but you can rest easy knowing they’re there… they’re like the passion, the shining [of the lives of the siblings].” They’re something that “make you happy just to know they’re around.”2

These penguins are a chaotic complement to Momoka’s radical love. Momoka befriends people who are seen as useless by society, or see themselves as such. Her love is guileless and simple, one could even say foolish. It puts her at risk for getting hurt by others, does lead to her getting hurt, even to disappearing from this world. As the raw essences of the Takakuras, the penguins emphasize how a similar kind of foolish love is at the core of their relationships. This approach resonates with Matsumoto Hajime’s celebration of a foolishness that puts the fool out of step with society. Misbehaving in public combined with absurd gregariousness with friends and strangers alike, though his hand of friendship is probably offering you a beer. And in fact, in the same interview, Ikuhara laments the decline of foolish characters in media. Freeloaders, fools, and other “useless” people in society challenge how society assigns value. The foolishness of love is loving someone or something for just being around in your life, all the more foolish when these relationships are inconvenient or difficult.

I think there’s something for anarchists to take from this kind of commitment. A commitment to commitment? “…the will to make the next link, hopelessly.” The will to see if you can stick out tough relationships, to develop relationships worth the trouble, to love each other foolishly. This is all to say, be like penguins. Or be like Momoka. Be like both. Better relationships by themselves aren’t going to bring about the end of this world, but as Ikuhara suggests, fraught as they are, these relationships can help us to not only survive, but flourish as we create spaces of possibility for the unpredictable and unforeseen.

1 We’ve seen this in Ikuhara’s works before—in Utena it was the etiquette of dueling, in Sarazanmai the characters fought kappa zombies and were paid with golden and silver plates—time and time again, characters submit themselves to a god (an idea, a logic that isn’t theirs) and with it the fantasy objects and logic of scarcity that give it the stuff of reality.

2 Mawaru PingDrum Koushiki Kanzen Guidebook: Seizon Senryaku no Subete.

Pingback: January discussion – Life Against Death – Viscera