“You must build the language

that you will live in.

You must build the house

where you’ll no longer be alone.

You must find the ancestors

who will make you more free,

and you must invent the new

sentimental education

through which once again,

you will love.”

–AND THE WAR HAS ONLY JUST BEGUN

My preoccupation with Flaubert has consistently been in relation to Madame Bovary, occasionally in relation to a gift of this novel or an insistence on reading the novels of Chris Kraus (whose works I frequently gift to others), to its multiple translations (I prefer the first English translation, done my Eleanor Marx), to its exquisite craftsmanship (Kraus relates that one can read this novel multiple times, and from there, learn how to write; perhaps it was the five years of Flaubert tedious labouring over this novel, the oftentimes full week spent on writing one page, or perhaps it is the themes, of lived experience and its relation to the mimetic function of romance novels, of debauchery, or of the fact that this novel was put on trial for pornography). In the past I had read other works of Flaubert, namely his last unfinished novel Bouvard and Pecuchet, and some shorter stories. I had known about Sentimental Education for over a few years, but only recently came across an old Penguin Classics edition a few weeks ago, and, in conjunction with a long-standing acknowledgement of what sentimental education is being referenced to in the above quotation, I began reading this somewhat droll but fascinating novel. This book essentially is a fictionalized autobiography of Flaubert’s own life in the 1840’s, as a young radical republican and as a pathetic romantic; it was one of the best-selling novels of the nineteenth century.

I had begun reading the novel during a recent trip to Santa Cruz, wherein I was paying a visit with romantic inclinations foremost in mind, secondly, a chance to see what the different milieus were presently interested with. I spent much of my time in this small city with anarchists who were marginally students, or had recently been students, most of whom could be divided into three camps; the primitivists, the anarcha-feminists, and the communist boys, all of whom I found lovely (even if I thought the divide was slightly unwarranted; for myself, as for a few others, the critique of technology and the abolition of the family and patriarchy are defining foundations of the communist critique).

Another brief interlude of anecdote in relation to Santa Cruz, was the meeting and curt break-up with an old friend, whom I had spent much time with in the past discussing Tiqqun, especially in this context the crude notion of “building the party”. This was a friend whom was one of the few that I confided in my thoughts concerning a new sentimental education as we sat across from one another at the Jury Room bar, chain smoking and drinking amidst our mutual torpor. Regardless, one of the last things I mentioned to them concerning Sentimental Education was the absurd continuities from the text to our own milieus; they probably thought me mad.

Sentimental Education traces the experiences, choices, and concomitant lifestyles of Frederic, a young middle class intellectual, with a pretty face (features resembling his mother), and an extreme penchant for the romantic (whether it be the taste for the barricades, or histories of Napoleon, or platonic lovers). The main character (Frederic) is placed in an interregnum of different worlds, that of the republican and revolutionary milieus, mostly lower-middle class, and that of high society, mostly upper-middle class (very little of the aristocracy, even if the main character has a claim to a title as such through his maternal family line), and marginally that of the art and literary milieus, cafes, revolutionary clubs, drawings rooms, the Paris streets, and rural life. The main character is deeply republican, which, in this novel, is essentially anyone “against Authority”; regardless of major differences of analysis every republican is waiting for the revolution, every republican has a million grievances, but, few parties of revolt are clearly delimited (again, the only point of commonality is that of “against Authority”; hence the immense confusion during the 1848 revolution with the side by side revolt of both proletariat and bourgeois, to the overall detriment amidst betrayal and slaughter of the former), excepting that of the Blanquist Societe des Saisons, which reappears amidst and on the margins of Frederic’s republican comrades, and also serves as a temporal register, as the almost annual insurrections of this society and its leaders undergoing torture in prison make it a constant reference point in political discussions. Frederic establishes himself in Paris, out of love for an art-dealers wife, enters into high society, doing little but living off his massive inheritance, constantly failing most of his friends expectations (his lower middle class friends, many of whom are studying to become or are already lawyers, all of whom detest the rich and the privileged; projects for revolutionary journals, for newspapers, for other literary endeavors, are always lacking funds, and Frederic, though promising to help, fails in the most pathetic of ways to do so, namely, coming short of funds owing to the purchase of expensive trinkets as gifts, wasting money on the stock market, lending massive sums of money to men in high society). He writes a little, and reads a bit, and spends his time in cafes or visiting high society ladies in parlours, making an overall favorable impression on nearly everyone he meets.

The majority of the novel, part II, is, overwhelmingly droll and tedious to read (even if the pacing is slow, there are abrupt incisions from one paragraph to the next, which take us to moments or days later in the narrative), and traces the major aspects of the story within its boundaries, namely, the choice to move to Paris, enter into high society, live fashionably, and maybe become a “man of state”, all solely to be closer to Madame Arnoux, whom the narrator falls irrevocably in love with at first glance, on a riverboat. Frederic, throughout a few hundred pages, never gets past declaring his love for Marie Arnoux, which tends to make the majority of the novel rather frustrating, both for the main character, and for the reader. Something needs to happen, but never does, until the end of this section, when Frederic instead finally succeeds at seducing Rosanette, whom he also platonically courted for years due to her proximity to Monsieur Arnoux. Part III opens onto an abrupt immersion into an insurrection, and, despite the insistence of Rosanette for Frederic to stay in bed, he immediately wanders out, and spends the day mingling with the mob, taking great pleasure in witnessing the barricade fighting, remarking upon how solid his own emotions are in response to his flippant indifference to the corpses (“he felt as if he were watching a play“), his great delight in running into friends of his (even the art dealer, Monsieur Arnoux, who mid-novel becomes a capitalist running a pottery factory, is there amidst the crowds in revolt, as a member of the solidly bourgeois National Guard):

“Fresh groups of workers kept coming up, driving the fighters towards the guard-house. The firing became more rapid. The wine-merchants’ shops were open, and every now and then somebody would go in to smoke a pipe or drink a glass of beer, before returning to the fight. A stray dog started howling. This raised a laugh.”

“An explosion of frenzied joy followed, as if, in place of the throne, a future of boundless joy had appeared; and the mob, less out of vengeance than from a desire to assert its supremacy, smashed or tore up mirrors, curtains, chandeliers, sconces, tables, chairs, stools – everything that was movable, in fact, down to albums of drawings and needlework baskets. They were the victors, so surely they were entitled to enjoy themselves. The rabble draped themselves mockingly in lace and cashmere. Gold fringes were twined round the sleeves of smocks, hats with ostrich plumes adorned the heads of blacksmiths, and ribbons of the Legion of Honour served as sashes for prostitutes. Everybody satisfied him whims; some danced, others drank. In the Queen’s bedroom a woman was greasing her hair with pomade; behind a screen, a couple of keen gamblers were playing cards; Hussonnet pointed out to Frederic a man leaning on a balcony and smoking his clay pipe; and in the mounting fury the continuous din was swollen by the sound of broken china and crystal, which tinkled as it fell like the keys of a harmonica.”

Flaubert does include some interesting events throughout this book, namely owing to the penchant for riots of so many of the main characters, as well as their reading tastes (the main characters closest friend since his school days, Deslauriers – “Deslauriers himself had abandoned metaphysics; political economy and the French Revolution now occupied his attention” – slightly recalls Karl Marx), the radicalism of politics of certain characters (“According to Mademoiselle Vatnaz, the emancipation of the proletariat was possible only through the emancipation of women. … Ten thousand citizenesses, armed with good muskets, could make the Hotel de Ville tremble.”), the intrigues of secret societies, and even, the eternally delayed and failed attempts at love affairs of the main character.

Sentimental education, past and present experiences to come

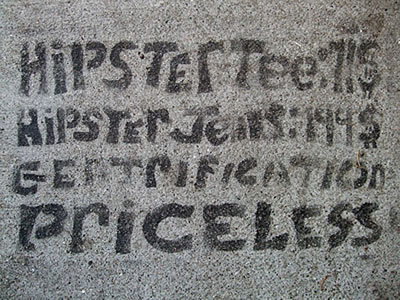

The anarchist milieu I occasionally inhabit feels strangely similar to that of the contradicting worlds of Frederic. Though my friends and myself are certainly lumpen (to some extent we are conspicuously part of that section of the working class which is most predisposed to crime, both as a means of living, and as a means of struggle), we might also be the only individuals left in this society who still play at living as the classical radical bourgeois: for instance, the overwhelming emphasis on calling on friends, on making of every living room a parlour space, of whiling away one’s time at cafes, gossiping about other members of society (our small milieu of friends and comrades) in different cities, gossiping about whom is sleeping with whom. Our own high-society is deeply déclassé in that we all portend to an existence which necessitates trust-funds, yet, none of us have this nor any other means to live off of without working, and though even if we sometimes manage to frequently obtain high priced items – fashionable clothes, organic foods, expensive beauty products, rare books – this is all owing to theft or larceny or food stamps or unemployment benefits, and not by our good looks. Calling on others in society is absolutely necessary to maintaining a position in the milieu (and if one is strongly evocative of intelligent yet easily digested strategy, then traveling and having parlour discussions is certainly very lucrative for making one’s positions resonate outwards), failing to do this for too long of a period of time, to fly (at best) or hitch (at worst) to other cities to visit friends for a few days or weeks, indicates that one is drifting away from one’s friends. Friendship revolves around a certain exquisite taste, a penchant for extremes; those who gift the most are considered the most charming; wanting to riot; and the sexual relations, either normatively limited and closed off (though one is always platonically courting everyone else) or, absolutely open to endless partners (which is why we are stupid little hipsters, as the hipsters of today would make Don Juan dizzy), with a fair touch of insipid and banal romance interlacing either, is what may or may not make us resemble the main characters in this novel.

With my lily-white hands I once started to write a few fragments concerning the insurrectionary anarchist milieu, and it came out as such: Some speak of “building the party”, alas, that fiction is a decade-long endeavor, stagnant form. Hence the remarkable inclination to act as if those in different cities are similar, friendly objects. But, as things only approximate the level of the cell or racket (a share of both), activities can only resemble that of the lowest common denominator, an absence of a cultivation of affects (our melancholic reading of Hiedegger pressupposes an absence of parrhesia), and an insipid existential-leninism (the hegemonic node of hierarchical social engagement programmed into every “revolutionary” milieu).

Attempting to address the same subject a few minutes later, I wrote: A milieu which is tiny, approximately “200” -or so the delusion goes- theoretical determinists, still set on voluntarism and the praxis of ‘77, on friendships and gossip, on silly mistakes and a form of conflictuality leading to a high amount to be disciplined not by the university, which would be expected of most of us at due to our age and bookish interests, but by the prison and judicial apparatus; I want my friends to feel agency, when there is none, and to traverse and supercede nihilism, which entails collectively elaborating the “historical avant-garde”. Objectively, I am playing a fine adventure, enjoying the faces of my untimely contemporaries, many of whom will be consistent collaborators on history, theory, and literature for some time to come.

A day later, attempting to address the same subject: It’s problematic though, as the milieu in question isn’t even a milieu, it’s not properly formed, not properly consistent, nor is it very definable, and rather resembles a “cool-kids club” dressed up in the false sincerity of politics. And though I should give some clear space to understanding a milieu-which-is-not-yet-a-milieu to the explicit critique of social-positioning and staccato signifiers (oh, they all dress like hipsters in their tight pants and black hoodies and leather jackets; oh, they all spout Tiqqun; oh, they’re all so “sexually liberated” because they’ve stepped into the waged ghetto of the porn-industry) which have come from those old friends of mine who at once feel incredibly comfortable (theory and feminism and anarchy: sure, why not!) and incredibly upset and detached and critical with this small IA milieu (“they’re nothing but cool kids with a penchant for exclusionary practices”), it still also makes sense to analyze these dynamics in the lens of a less social, and more structural way. Which, unfortunately, pushes me to hold others to the highest standards, even if those standards for collective practices end up revealing my own penchant and taste for an extreme voluntarism.

What would a new sentimental education, as a literary device, and as a hybrid assemblage or quilting point of pathways of revolt and lived experience(s) opening onto desubjectivation and the commune, look like? A text on experiences which lays bare the current situation and constitutive fabric of the various worlds we inhabit; that apprehends a lucid survey of the historical conjuncture through the past few years of events; that clarifies how we can understand even the most trivial aspects of our lives, and of our affective relations, in relation to what gives force to overturning and passing through a phase of collective nihilism. I’m not so sure if a literary elaboration upon the current figures of our shared narrative – a collection of characters who have experienced summit-hopping, the green scare, student occupations, or a hundred riots – can even match up for a figure which clearly illuminates the situations and relations of forces of all our milieu(s), of the worlds we inhabit, of our passing whims, and of our most consistent gestures and penchants. I’m not so sure that the figure of a young (anti-state communist/insurrectionary anarchist) intellectual who works odd jobs and goes off to other countries to riot and hang out with friends and work on literary projects for more than half of each year is the figure of our time. And I’m not so sure that the anarchist milieu(s) in various cities, and specifically those I oftentimes inhabit, are the avant-garde of dissolution, though it would be more than interesting to suggest that we could try to be. Regardless, something amidst these scattered traces of a proximity to the angelic and the melancholic will find its understanding and reconciliation, though to prevent the unseemly tact of the theoreticians posthumous grimace from taking hold when we are already dead (and as Kathy Acker says, Dead Writers don’t Fuck), we need to invent a new sentimental education, one perhaps rooted in a relentless experimentation, through revenge and sacred conspiracies, or rooted in solitude, opening onto unlimited hospitality and friendship.

…

There is still much unmentioned in this review that would make of this a proper literary essay. To step to the side of the above tautologies concerning a milieu, and for a further construction of an analysis of this novel, it would be of interest to engage with: a theory of whims, reflecting both upon the transitional moments of the structure of the novel and those of the protagonist’s wanderings and engagements; a literary topography, namely the spatial mapping of Paris and its outskirts (1), a cartography of secret societies, and a historical and spatial envisioning of the protagonist’s encounter with the events of 1848; the prioritization of a penchant, namely the fundamental truth-axiom of love, a fidelity-towards-the-event of the protagonist; a theory of dross and of readerly boredom; a reading of reaction and counter-revolutionary affects as evidenced by the sundry transitions of the novel’s character in the aftermath of 1848; also, a theory of the dandy.

Notes:

(1) A rudimentary form of a literary map now exists for Sentimental Education online at: http://www.communitywalk.com/sentimental_education_map/map/347582