This review started out being about Sweet Tooth, the tv show, with a focus on the whiplash of going from the horror comic to the live-action cartoon show. I will talk some about that, but it’s not surprising that a tv show inject pastels into the veins of any original work, especially indy or underground, so my pique may be justified but is also old news.

But the show gave me a bad taste in my mouth before I had even looked at the original comic, so I spent some time wandering around, trying to figure out what it was about even the opening scenes and narration that set me off.

And, it turns out, I’m going to talk about race again.

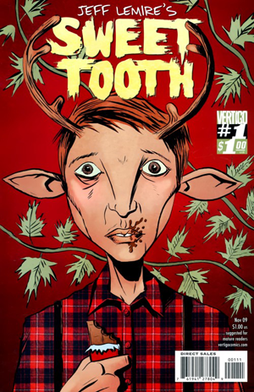

Let us back up. Sweet Tooth is first a comic book, drawn in a grotesque style lacking prettiness of any kind. It includes prostitutes, mercenaries, self-destructive drunks who’ve abandoned the things they hold dear. The eponymous protagonist is not especially charming or empowered, although he is still important (for who he is rather than what he does), and is one of a breed that is being hunted. There is a step-dad relationship with a tough guy who betrays him and then tries to make amends.

An example of the artistry: In the comic we learn the history of the protagonist as, hypnotized, he relives his past under the direction of a bad guy. We are immediately implicated, since we are put in the position of this bad guy, learning this history as he does. (This bad guy wants to do good, and believes that he can do good by torturing creatures, the obvious corollary being animal experimentation—something that most of us have benefited from, whether we want to or not. So there are levels of implied collusion here, in some effective horror writing.) Even what could be considered Sweet Tooth’s innocence in this process is mitigated by his collaboration with his abusers, who are murderers/genociders or collaborators themselves.

In the show, the most meaningful characteristic that Sweet Tooth has is the capacity for people to protect him for no apparent reason. He cutes at them and they bend to his will, compelled by the power of His Innocence. Ignorance and innocence are deeply combined in western civ, from the bible on, and Sweet Tooth in the show seems to be innocent entirely because he’s ignorant, which leads down some curious roads. Who else wants to be innocent while claiming, even embracing, ignorance? More on that later.

In the comics, the tough guy is next in importance; he has an arc, and the reasons why he sacrifices for Sweet Tooth are explained, reasons that might be predictable but at least make some sense. (There’s even something consistent about the predictability, in this world that is partly about the banality of evil: the tragedy of our stories does not come from them being unique.) We learn about his motivation after he’s betrayed the protagonist, after he’s been beat up, after he’s tried to kill himself.

In the series (which has only one season, but will have more), there is no real betrayal. There is no character arc. Sweet Tooth’s companions work their hardest to protect him from every cruel reality, including the consequences of his own thoughtless behavior, like when he loses life-sustaining medicine required by the tough guy, now his protector, who basically just shrugs off this loss. Sweet Tooth is the only character who gets any kind of development, which makes for a shallow story, and also implies that a) only young people are important, and b) only young people can change or grow.

Again, Sweet Tooth the comic is a horror title. The drawing style is awkward—explicitly un-cute; it precludes even the possibility of prettiness. The drawing is raw and sparse, which is appropriate to the content. People are murdered, there is gore, brutality, betrayal, religious extremism, greed, exploitation, lack of choice, slavery, etc. The comic is one scenario after another of going from the frying pan to the fire, of the only option being a destruction that comes sooner or slightly later; of almost everyone being complicit either actively or passively. This is a meaningful if horrifying reflection of our world, in which privilege is a veneer of good living shellacked over gaping genocides, torture, and misery.

Ok, having a hard couple of years here, but I’m just sayin’.

Sweet Tooth the series is saccharine fantasy. Landscapes are pretty, people are clean and cute (except for the bad guys, of course), most especially Gerber-Baby Sweet Tooth. It’s the least gritty dystopia we’ve ever seen. The protagonist is protected by characters who care about him, again, for no apparent reason. The narration from the beginning emphasizes how special and important Sweet Tooth is, so there’s a whole Chosen One vibe going on from the very first. The show brushes against the idea of bad things, bu there’s no sense that anything really bad will happen—that field of deadly flowers will kill you and so no one goes there, but that’s easily worked around by an ad hoc face mask and some running, which apparently no one ever thought of before…

So ok, the show has dramatically, foundationally changed the comic. What else is new, right?

As I said, when I started this, I thought I would focus on that shift (comics to video), and what that looks like when done well, or at least, common failings that we could learn from. But I found myself preoccupied by race, specifically what it meant that the series changed the race of the main secondary figure, making the step-father-figure Black rather than white; what repercussions that had, and what the coloring of content generally means, in the on-going racism of this world.

One of the ways that shows include people of color is through a token, a character who may play an important role, but is the only person of color of significance, sometimes the only person of color at all. This tends to preclude that that character will ever do anything bad, and that, of course, means superficial characters, boring writing, and trivialized problems. Aside from the obvious racism of making the only person of color a bad guy, which doesn’t (I hope) need to be talked about, the most common attempt to include people of color (As the only significant person of color in Sweet Tooth-the-show, we know that the tough Black guy will not do anything meaningfully bad, certainly nothing like the kind of betrayal that happens in the books. If he does something even mildly bad, anyone with any literacy in television will know that he will make amends. That means, no tension. We never believe that he will turn out to be anything but a good guy. Probably the show’s decision makers decided to make a non-challenging show first, but the casting of a Black man for a role that had been violent, desperate, and mercenary, was part of that decision to make the show at best merely entirely different from the comic, and at worst, tediously shallow. The fact that this character is supposed to be an intimidating fighter, and was cast as a dark Black man is again stereotypical and embarrassing.

Contrast that with a show like The Irregulars. I’m not saying The Irregulars is a good show. It’s not well written or acted, nor does it play especially cleverly on the exhausted foundation of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes (though it does try, being a dramatic re-imagining that empowers the proletariat or some such). But in terms of race, it does pretty well, given that we all have very low expectations of Hollywood. The Irregulars has a cast of multiple people of color, including the use of a Black actor (admittedly, the darkest on the crew) as one of the bad guys. But this actor, Clark Peters, is best known for playing a good, solid, respectable guy, which means that even as his bad guy arc plays out, there is a tension about whether he really is bad, and that tension alone makes the show better–philosophically, socially, artistically, and emotionally–than the pablum of Sweet Tooth-the-show.

Sweet Tooth-the-show takes a story that is about a new world, in which people bump up against each other while terrible things are happening, and in which whatever good things might happen will mostly be accidental, and turns it into yet another Messiah Story, in this case mixed with The Children Will Save Us. My main read is that the show represents white people’s, maybe mostly white men’s, desperate hope that they have something to offer others, something in their very lack of analysis, their ignorance, their absolute determination not to see the world as it is, those lacks that get called innocence, and promoted as some kind of charm, some kind of sweetness, some kind of saving grace, as if wile e. coyote’s mid-air understanding is the problem, rather than whatever collapsed the ground under his feet.

There is another read of Sweet Tooth-the-show, which is that it’s about parenting in a difficult world. That its appeal comes from the desire that some adults have to protect [their] children from ugly realities, that the creation of the stage of life called childhood1 is about the desire and occasional ability to protect children from hard things that happen every day. This read puts the woman and man who protect ST in the series in the position of parents (whereas in the comic there are multiple adults eventually traveling together with the protagonist). This is a slightly more sympathetic read, one that could play off the special abilities of ST and his generation as the potential of children to bewilder, surprise, mystify, and play outside the boxes of preceding generations, even if that still puts kids in the position of saving the world, and kids are still primarily represented by a white boy.

While the comic is inarguably dystopic, it is paradoxically more hopeful than the series. The very harshness of it is hopeful on a different level. Horror implies that we are strong enough to look at what is happening. The arc of the protector in the comic reflects the capacity of broken people to grow and change and make different decisions. The series, on the other hand, is candy that might be easier to swallow, but will rot out our insides.

- Childhood is generally considered to be either a natural biological stage of development or a modern idea or invention. Theories of childhood are concerned with what a child is, the nature of childhood, the purpose or function of childhood, and how the notion of the child or childhood is used in society. The concept of childhood, like any invention, was forged from a potent relationship between ideas and technologies within a frame of social, political, and economic needs.