Böll, Orwell, Bolaño: In Defense Of Art

This is a century in which democracy regularly presided over the birth of fascist regimes and civilization constantly rhymed – to the tune of Wagner or Iron Maiden – with extermination.

-The Invisible Committee

Only in chaos are we conceivable.

-Roberto Bolaño

Introduction: Art and Auschwitz

In the book Music of Another World, Szymon Laks describes his experiences as a member of the Jewish orchestra in Auschwitz. The post-war, communist government of Poland would not allow it to be published, claiming that it portrayed the Nazis in a positive light. In the book, there are passages such as the following:

When an SS-man listened to music, especially of the kind he really liked, he somehow became strangely similar to a human being…at such moments the hope stirred in us that maybe everything was not lost after all. Could people who love music to this extent, people who can cry when they hear it, be at the same time capable of committing so many atrocities on the rest of humanity? There are realities in which one cannot believe.

The book was eventually published in France and is one of the only books on the subject of the Jewish orchestra in the death camps. Laks explains how playing in the orchestra allowed him to have extra food, more privileges, and was the sole reason for his survival in the camp. He does not hide from the fact that his art sheltered him from extermination, nor does he hide his belief in the eternal power and beauty of music.

Contradictions were unavoidable. The book I present to readers interested in these matters does not claim to solve them. On the contrary, it may even introduce a few new contradictions. Is not one of them the very fact that music—the most sublime expression of the human spirit—also became entangled in the hellish enterprise of the extermination of millions of people and even took an active part in this extermination?

Laks never lost sight of the power that the art of music contained and his experiences in the death camp did not ruin the faith in his craft. But it did show him how his craft could be used for the most brutal and deathly purposes, how his compositions could ease the worries of those who did not know they were walking into the gas chamber, and how music calmed and cleared the minds of the Nazis who starved, shot, and burnt thousands of people in Auschwitz.

To write about music in [Auschwitz]–Birkenau without referring to the background against which this music was played would be counter to the aim and even the sense of this book. For this is not a book about music. It is a book about music in a Nazi concentration camp. One could also say: about music in a distorting mirror.

Heinrich Böll and the Red Army Faction

Heinrich Böll worked for a bookseller after completing school in 1937, four years after the Nazis had risen to power. The bookseller he worked for sold contemporary and antiquarian books and also published select works. After finishing his apprenticeship with this book company he attempted to devote his life to reading, writing and teaching. This lifestyle was interrupted by his conscription in the Nazi program of compulsory labor service. Completion of this six-month service was a prerequisite for attending university. Having fulfilled this requirement, he decided to attend university but was only able to complete the summer term before being conscripted into the German army in 1939.

He fought for the Nazi army until 1945 when he was captured by the Americans and interned in a French prisoner-of-war camp. Released in the winter of 1945, Böll returned to his home town of Cologne to find it destroyed by the allied bombing campaign. There, he began to rebuild his demolished house with his wife. Like millions of young German men, Böll had been swept into the clutches of the fascist army and did not attempt to escape. Like millions of young German men, he spent the rest of his days after the war attempting to understand what had happened in Germany and how it had come to pass. His first novel, published in 1949, was titled The Train Was On Time and centers on a young German soldier on a train ride from France to Poland, the country of Auschwitz. On the train ride, this soldier befriends other soldiers and they discuss the horrors of what they have seen and what war has done to them. But nevertheless, the train arrives on time and the soldiers continue onward into death, misery and war.

Unlike most Germans who had a hand in the war, Böll did not shrink away from his responsibility to those who had died but also to the new generation being raised in the reconstruction. All of his following work concerns the German psyche and the aftereffects of fascism. In his fiction he highlights who was responsible for the Nazi horrors, explains how Germans attempted to resist, and casts a light on the many who were cowardly and afraid. For this, he earned the reputation of being an antifascist author and is credited with redeeming German literature from the shadow of the Nazis.

In April of 1968, the first members of what would become the Red Army Faction (RAF) bombed two department stores in Frankfurt, wanting to show the German public that they could not support American fascism without being subject to attacks. These young people had internalized the messages that people like Böll had been sending to the youth since the end of the war. They looked on with disgust and horror at the former Nazis holding high positions in the government and corporations of capitalist West Germany. Holding onto the memories and stories passed down by Böll and other writers, the youth were determined to never forget nor forgive the people who had created the death camps.

However, there were others who did not share either Böll’s or the youths viewpoint. Axel Springer, owner of the Bild-Zeitung newspaper, championed German support for the American war in Vietnam, condemned the wave of student unrest, and singled out radical leaders by name.

One of these radical leaders was Rudi Dutschke and after the Bild-Zeitung ran the headline STOP DUTSCHKE NOW! there was an attempt on his life by a right-wing youth. In retaliation, a mob of people stormed the newspaper headquarters, destroyed their trucks and burnt their papers. Amongst this mob was Ulrike Meinhof, the famous journalist who in 1970 helped free Andreas Baader from police custody and joined the RAF.

Unlike his contemporary Theodore Adorno, Böll met the younger generation where they were and did not assume an arrogant and condescending demeanor. He watched and did not condemn the RAF as they proceeded to rob banks and attack military and judicial targets. One of these targets was the offices of Axel Springer’s publishing company in Hamburg. In 1972, an RAF bomb exploded in an office and wounded 17 employees of the company that published the Bild-Zeitung newspaper. Ulrike Meinhof, the former journalist, was largely behind this action that would linger in Böll’s memory.

In the summer of 1972 the first generation of the RAF was captured and soon began their hunger strike in prison. Böll intervened on behalf of Ulrike Meinhof in 1972 because he believed that the press, which had been accusatory, had deprived her and her group of a fair trial. Böll was then himself criticized, subject to police searches, accused of creating a climate for violence, and cast as a threat to the internal security of the nation (Anonymous).

By 1974, an RAF member named Holger Meins had died from starvation. This same year, with the actions of the RAF firmly in the popular imagination, Böll published one of his greatest works. The Lost Honour of Katharina Blum or: how violence develops and where it can lead is a slim novella only 144 pages long. It details the life of Katharina Blum (pronounced ‘bloom’), a young, stern housekeeper for a wealthy liberal couple.

She leads a boring life, wanting nothing more than to earn her wages, balance her checkbook, have an apartment, own a car and be able to cook herself dinner. She is portrayed as the perfect example of the moderate success and comfort that was awarded to those who worked hard in the new capitalist West Germany. One day, she is invited to a dance where she meets a young man. For the first time, her friends see her enjoying herself and dancing. The normally stern woman unlocks herself and goes home with the young man who also happens to have stolen money from the army and deserted.

The next morning, the police raid her apartment in search of a dangerous terrorist. When they enter the apartment, they find Katharina alone with a smile on her face. The authorities take her to the police station and begin to interrogate her, believing that she helped the terrorist escape. She maintains her innocence and narrates to them her banal life. Unable to find any evidence against her, she is released into the world but soon becomes the victim of a right-wing media frenzy.

A paper called Die Zeitung calls her and her mother communist agents and encourages the authorities to jail her. A journalist for the paper illegally visits Katharina’s mother in the hospital and through his words causes the old woman to die of a stroke. His presence in the hospital is never discovered but upon hearing news of her mother’s death, Katharina blames it solely on the right-wing journalist. She soon invites him to her apartment for an exclusive interview. After he arrives, Katharina shoots and kills the journalist, turns herself into the police and learns that her young terrorist lover has also been apprehended. The reader last sees Katharina locked up, happy to be able to be with her first love once they are both released from prison.

In this novella, Böll in no way portrays Katharina’s assassination of the journalist as either faulty or uncalled for. If anything, this action is presented as perfectly reasonable. The novella caused an immediate controversy and positioned Böll on the side of the anti-fascist RAF. In 1975, the year after the novella’s publication, the second generation of the RAF began its offensive. Some would accuse Böll of encouraging and allowing this to happen. In this authors estimation, Böll is a true anti-fascist artist. His book was perfectly timed and posed the most forbidden questions in West Germany. A cinematic adaptation of the novella was released in 1975, further adding to the conflict. The film ends with the following words that were written by Böll at the beginning of his story:

The characters and actions in this story are purely fictitious. Should the description of certain journalistic practices result in a resemblance to the practices of Bild-Zeitung, such resemblance is neither intentional, nor fortuitous, but unavoidable.

George Orwell and the Sect of Revolutionaries

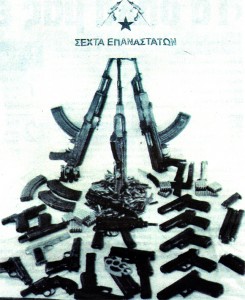

Shortly after the Greek insurrection of 2008, a group was formed that called itself Sect of Revolutionaries. In February 2009, after shooting at a police station and throwing a grenade at it (which did not explode), the group claimed the action by putting a CD with their communique on the grave of Alexis Grigoropoulos. In the communique, they threatened to assassinate police officers. This threat was followed through with and in June of 2009 the group killed an anti-terrorist police officer. In their communique for the assassination, the group threatened to attack the journalists responsible for helping quell the insurrection and returning society to its normal functioning. In July of 2010, the group assassinated the right-wing journalist Sokratis Giolias outside of his home. The following text are excerpts from the communique claiming his assassination.

So we’d rather go to his home than let something happen in a gunfight in the street and hit someone irrelevant. What exactly was said through the intercom to ensure not only that he would come down, but would come alone without being accompanied by his wife, is something that does not need not be made public for several reasons.

Our main concern was for not the slightest thing to go wrong with his wife and of course the young child. Everyone gets the end they deserve and these people have done nothing to us. Furthermore, the practice of political execution is very clear and specific. There will never be any danger from our attacks for any family members or family environment of a target that does not have any involvement in their dirty options and interests, even if this obliges us to cancel our plans. An urban guerrilla is not a cold murderer. When he chooses to shoot, he does not hit the face itself, but the choices of the specific person, the position he holds, the decisions he has taken, the interests he serves. It’s not a personal thing. The armed fighter fights the operators of the system who no longer have their own separate face, but a particular job they are defending. The armed fighter does not shoot people, he shoots against the system itself.

George Orwell, perhaps one of the most famous anti-fascist writers, was also a journalist. After being shot in the neck fighting against Franco’s army in Spain and after witnessing the Stalinist betrayal of both the anarchists and the Trotskyists, Orwell returned to his native England and penned the immortal work Homage to Catalonia. While he recovered and wrote, hardline communist supporters began to attack him in the press, insinuating he was nothing more than a bourgeois tourist who used the misery of others to sell his books. When his reflections on Spain were published in 1938, no one bought the book and it was clear that his perspective was neither welcomed or believed by those who subscribed to either the capitalist or communist mythology.

The second world war began in earnest in 1939. Orwell made his living during this time by writing for newspapers and magazines while his wife worked for the Censorship Department. As the Luftwaffe began to bomb England, Orwell saw the same fascism he had been fighting in Spain turning its sights on the island. He and other radical socialists joined the Home Guard, believing it could become a revolutionary organization. However, mishandling of a mortar during training caused Orwell to injure two fellow militiamen. Following this, he contributed to the war effort by planting potatoes and writing antifascist articles. The struggle against the shared fascist enemy had brought him to this position of co-existence with the British Empire, although he never accepted it uncritically.

In the summer of 1941, Orwell began working for the BBC, transmitting broadcasts to India in order to counteract Nazi propaganda while his wife transferred from the Censorship Department to the Ministry of Food. In 1942, Orwell started to write for the Tribune, a paper run by two leftist Labour MP’s. Wanting to concentrate on writing his next book and tired of sending useless broadcasts to India from a decaying empire, Orwell quit his job at the BBC and became the full time literary editor of the Tribune. His new book was to be Animal Farm.

By 1944, the book was ready for publication. Unfortunately, no one would publish it, afraid that it would damage the vital wartime relationship between England and the USSR. Shortly after the first rejection of his manuscript, a V-1 rocket destroyed his home and he had to dig through the rubble to retrieve his book collection. After Orwell finally found someone to publish his work, the Ministry of Information instructed the publisher to deny publication (it was later discovered that the official in the Ministry who ordered this was a Soviet agent). In 1945, Orwell found another publisher who promised to publish Animal Farm and was later sent to Paris to cover the liberation of the city for the Observer. While he was there, witnessing the destruction of the Nazi occupation and the rebirth of the city, his wife died during a hysterectomy.

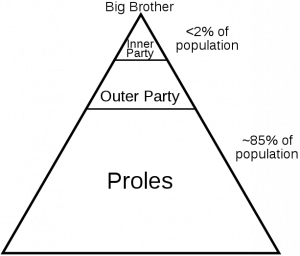

During the first General Election since the start of the war, the Labour Party took control of the government, ousting the conservatives led by Winston Churchill. The month after this election, with the leftist Party in control of the country, Animal Farm was finally published. Orwell quickly found himself with the reputation of being an anti-communist writer. While Animal Farm was a definitive condemnation of Stalin’s USSR, he soon turned his attention on the Labour Party and the Cold War that was about to start. He began work on 1984, his bleak and terrifying tale of the future. He and his wife’s experiences working for the government informed much of the story. What Orwell feared the most was the Labour Party imitating the practices of the Stalinist’s in their effort to fight against post-war Soviet expansion. His vision of the Ingsoc (English Socialism) of the Party (the Labour Party) was a horror he wished to avert.

The main protagonist of the story is Winston Smith, an underling for the Outer Party. This character is Orwell, forced into collaboration with the Inner Party out of wartime necessity. Orwell saw the lies, the deception and the corruption of the government he had worked for during the war and in his final days of writing 1984 he did his utmost to apologize and to explain the position he had filled during the conflict. He did not shrink from what he had seen or what he had done and with the publication of his book in 1949, he gave everyone a warning of what the powers of the world intended to do over the next 40 years. His book may have not been so bleak, he said, had he not been a dying old man.

It is unknown what Sect of Revolutionaries would have thought of Orwell had they been his contemporaries, especially during the war years. He most certainly collaborated with the government and did support the Labour Party, however critically. When he died in 1950, he left behind a legacy that would inspire countless anti-fascists and writers. One of these writers, Roberto Bolaño, wrote the following words about Orwell:

George Orwell isn’t just one of the great writers of the twentieth century, he’s also first and foremost a good man, and a brave one.

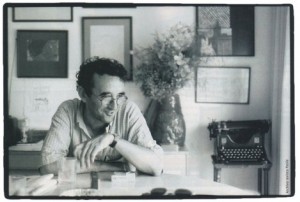

Roberto Bolaño and Exile

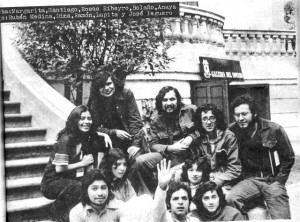

Roberto Bolaño was a silver-tongued demon of the written word and specialized in generating mysteries that confounded all who attempted to control the chaos of the imagination. Born in Santiago, Chile in 1959, Bolaño lived in the colonial city until his family relocated to the sprawling metropolis of Mexico City in 1968. That year in the city, over 300 students were massacred by the military at the Plaze de la Tres Culturas. This event, so traumatic and overwhelming, cast a shadow over the young people of the city that Bolaño was to call his home for the next 5 years.

From the age of 15, Bolaño began his life as a free spirit and vagabond. He dropped out of school and immersed himself in the leftist counterculture that was attempting to regroup after the bloodbath. He began to steal books by his favorite authors, attended poetry readings and learned the ways of the prostitutes, junkies, poets and gangsters of the Mexico City streets.

If we are to believe what Bolaño wrote, then the following narrative of his life is true. In 1973, at the age of 20, Bolaño left Mexico for Chile to go help fight in the war against capitalism. Salvadore Allende, the socialist president of Chile, had been withstanding international and domestic pressure after his election and it was clear to many in the country that a military coup or fascist revolution was approaching. Bolaño had only been in the country for a few months when Augusto Pinochet staged his coup against the government. While on the street, Bolaño was picked up by the fascist police and taken to jail. During his imprisonment, he heard the sounds of people being beaten, tortured and killed. After eight days in which he thought he would meet the same anonymous death as hundreds of others, Bolaño was discovered by two prison guards who had been his childhood classmates. Released into the now pacified and quiet streets, Bolaño decided to return to Mexico by land.

He wandered Central America during this journey and eventually gravitated towards the pockets of resistance still fighting in the war against capitalism. His path took him through Nicaragua and El Salvador where he saw that his revolution was not yet gone, that his contemporaries were still intent on freeing their countries. Returning to Mexico City in 1974, Bolaño committed himself to writing poetry and destabilizing the established literary order by interrupting readings, stealing books and attacking those he believed represented the conservative values that had lead to the carnage of 1968 and 1973. He was not a fighter or a guerrilla and his words were far more powerful than any sacrifice of his body could have been.

In 1975, Bolaño learned of the death of Roque Dalton. Dalton was a poet and a guerrilla fighter in the People’s Liberation Army, a Marxist organization fighting the government in El Salvador. Dalton believed, contrary to his comrades, that their clandestine existence prevented them from even knowing the people they claimed to be fighting for. This belief of his was later used against him by his enemies. A story was propagated that he was a CIA agent and his desire for his organization to be more visible led his comrades to execute him on May 10th, 1975. Dalton wrote, my veins don’t end in me but in the unanimous blood of those who struggle for life. His veins extended to Mexico City where Bolaño was attempting to create the Infrarealist poetry movement. In 1976, he penned the manifesto of this group from which excerpts can be read below.

In architecture and sculpture the infrarealists start from two points: the barricade and the bed…the true imagination is that which destroys, elucidates, injects emerald microbes into other imaginations. In poetry and in whatever else, the entrance into the work has to already be the way into adventure. Create the tools for everyday subversion…risk is always somewhere else. The true poet is the one who’s always letting go of himself. Never too much time in the same place, like guerrillas, like UFOs, like the white eyes of prisoners serving life sentences…make new sensations appear—Subvert daily life.

But the most haunting sentence of this manifesto appears near the end and encapsulates the disillusion and loss he and his generation felt in the time period between 1968 and 1975: We dreamed of utopia and woke up screaming. We hear in this line the cry of Dalton as he was executed and the screams of the Chilean disappeared. In 1977, a year after writing this line, Bolaño left Latin America for a post-Franco Spain, the place he would spend most of his remaining life.

In the old anarchist stronghold of Catalonia he worked a series of random jobs including being a garbage man and the security guard of a campground. Regarding this period of time in his life, Bolaño wrote, my sickness, back then, was pride, rage, and violence. Those things (rage, violence) are exhausting and I spent my days uselessly tired. I worked at night. During the day I wrote and read. I never slept. To keep awake I drank coffee and smoked…tacked up over my bed was a piece of paper on which I’d asked a friend from Poland to write, in Polish, Total Anarchy. I didn’t think I was going to live past thirty-five. I was happy. In the early 1980’s, Bolaño eventually settled in Blanes, a small Catalan town on the coast. He opened a jewelry store in which he also slept at night. This was the last of his “extra-literary” jobs and it enabled him to write his poetry with more consistency and less exhaustion and for the next decade he wrote poetry and made no money off it.

In 1990, his first child was born and he decided to begin writing fiction, the only form of his craft that would enable him to support his family. It was only after beginning to write novels that Bolaño’s experiences and his anti-fascism were articulated for the world. His second novel, Nazi Literature in the Americas, is a fierce condemnation on every petty writer that surrendered or willingly gave their services to the fascist governments of Latin America. The book is composed of various biographies of fictional authors who sometimes bear a resemblance to the living and dead authors that Bolaño despised. One of these characters is the son of fugitive Nazis who settled in Argentina after the war. He becomes famous for his line drawings that can only be seen from the air. These drawings are nothing more than the blueprints for concentration camps. Not surprisingly, the art world comes to adore and praise this silent and enigmatic fascist.

Bolaño’s next novel, Distant Star, explores this same theme by centering on the life of one of the authors described in his previous book, a Chilean named Alberto Ruiz-Tagle . The main character is a mysterious student of literature who always appears to be bored. When the fascist coup takes place, Ruiz-Tagle brutally murders two sisters he was in class with and takes pictures of his crime. Once Pinochet’s government is firmly in place, Ruiz-Tagle joins the air force and soon becomes a famed artist. His craft consists of writing cryptic phrases in the sky with the exhaust of his plane. This brings him much critical acclaim and allows him to traverse the high-society of fascist Chile. At one of his exclusive art-shows, he covers an entire apartment in photos of the people he has tortured and killed over the years of Pinochet’s reign. The high-society that sees these photos reacts negatively to these images of what allowed their fascist leader to rise to power. The novel ends with a private detective tracking down an aged Ruiz-Tagle in exile and assassinating him.

In 1998, Bolaño published The Savage Detectives, the story of his comrades and fellow poets in Mexico City. It details the divergent paths he and his friends took and reveals the love he had for those years of sex, drugs, filth, and beauty. The book’s plot spans across Latin America and Europe and centers on two characters, one of them Bolaño and the other his friend Mario Santiago, a member of the Infrarealist movement. The love and warmth evoked in this work that immortalizes his comrades quickly made the book Bolaño’s first best-seller and brought him a fame he had never known. But unlike many other artists who had allow their fame to devour and weaken them, Bolaño continued to write novels that focused on the deaths and misery caused by the fascists and the beauty, chaos, and art that he and his friends had championed.

His next novel, Amulet, focuses on the life of a woman who is trapped in a bathroom of a university for twelve days during the 1968 student massacre in Mexico City. While she is terrified and afraid and waiting for a death that does not arrive, she reminiscences about her life as the queen of the streets and poetry and highlights the creative world that the fascist military wanted to exterminate. By Night In Chile, a novella published in 2000, revolves around the hypocrisy of the church, the left, and the literary society that existed in Chile during the reign of Pinochet. These two books are attacks on all of the artists who lived comfortably while other artists, the poor ones, the rebellious ones, were slaughtered.

His final novel was 2666. This work transcends anti-fascism and expounds on the mysteries of the holocaust, Germany, the femicides of Ciudad Juarez, telepathy, the labyrinths of literature and the horror of unrestrained greed. It is the first and only great book of the twenty-first century and cannot be summarized. It is meant to be read carefully and with caution.

In his short story “The Murdering Whores,” Bolaño tells the story of a young woman who is watching the broadcast of a soccer match in what may or may not be Francoist Spain. She sees a young man give the fascist salute along with thousands of others during the match. For some reason she singles him out, dresses up like a whore, gets on her scooter and drives down to the stadium. Miraculously, she finds him, seduces, takes him to her apartment, ties him up and then begins to deliver a long monologue. Her words ramble and flow in all directions and the true reasons for what she chooses to do are never fully articulated. But at the end of the story she kills the fascist youth with no regrets and no hesitation. This image of a woman killing a fascist represents the utopia of Roberto Bolaño.

Coda

In the article “Gaga, Bowie, Hitler,” this author set out to disparage and undermine a few of those artists who used their gifts to bolster the machinations of fascist systems of governance. In this article, we fulfilled a suggestion from Heinrich Böll in which he stated that “to condemn [poetry] requires that it first must be recognized.” However, rather than follow his advice uncritically, we decided first to condemn art before recognizing its timeless power and beauty. Art has been praised enough, art has been abused enough, art has been mutilated enough. We felt no need to accord it any more undue praise.

An artist only has their commitment to their vision to hold on to. Once that vision is contaminated by the dictates of the market, authority, and the status quo, the artist becomes a tool, an empty shell, a plastic vessel. But there are artists like the ones described above who not only possessed but held onto a unique vision of a world free of fascism and control. Art can be a weapon and the authors described above demonstrate this assertion. Despite our harsh condemnation of art in the past, we agree with Roberto Bolaño that “only poetry isn’t shit.”

I miss my years of sex, drugs, filth, and beauty. These days I’ve replaced my old social life with comments on random blogs, and reading old essays/books/speeches of Luxemburg, Einstein, some Orwell & MLK Jr. I can’t handle Marx. I think its the beard. I can’t take anybody seriously who looks like santa claus. Plus, his obscurantism.. not my thing.

I like simple shit. Like Hemingway. I like my equilibrium.. punctuated.

Thanks for filling me in on more of Orwell’s life. About 40/50ish blogs I’ve surveyed so far that mention him are ultra-right religious neo-con “plandemic” conspiracy Faux Noosers. A lot of them post “dank memes” showing how Marx is actually Satan. And believe it- literally. They say the radical left is using our Newspeak to censor them. What they mean is “some corporations make more money by deplatforming us than keeping us around, and thats vewy scawwy.”