“The harmony of the seasons mocks me. I spend hours watching the sky, the lake, the enormous sea. This world. I feel that if I could understand it I might then begin to understand the creatures who inhabit it. But I do not understand it. I find the world always odd, but odder still, I suppose, is the fact that I find it so, for what are the eternal verities by which I measure these temporal aberrations?”

John Banville, Birchwood

It’s getting colder here. People shuffle by in hats and scarves. Fur-lined hoods appear in improbable quantities. Licensed vendors, unpacked in pleasant arrays, marshalled forth by the city in its brave quest to claim a new pedestrian shopping zone, are the first and only line of battle against the cold. They rub mittens and hunch puffy jackets against it, smile as only ascendant shopkeepers can, and roast chestnuts, slice baked goods, fetch glittery necklaces from crowded displays, and conquer what would have been a winterbarren street.

I used to be a partisan of winter, back when the seasons still promised an untamed difference. Now I too huddle against it, my fire gone, protected by an old leather jacket I found, waiting in just the right size, in a freestore near here. My friends made jokes about it, a throwback to the ’80s, evidently. When their jokes continued from time to time, I gathered they were actually made uncomfortable by my wearing of the jacket and its extinguished aesthetic.

The commodity demands its homage, even from those who must steal it. And my friends, anticapitalists to a one, go about in those sporty jackets made from materials far more polysyllabic than leather. Again the old question. Is it better to blend in, or to signal our defiance of the national religion? For myself, I just can’t turn down a jacket that still works, and my brain won’t accept that the dull brown thing actually draws attention from the citizens sunk in layers of equally mundane garb, hiding away from temperatures that still have not passed freezing.

This is a frigid race, with few defenses against even a lackluster winter. Nonetheless, this year there are fewer gloves in evidence. More people are keeping their fingers free to tap on little screens, their faces awash in blue glow, as they scuttle blindly down the streets.

The new device is finally triumphing in this economically holdout nation. Could anyone ever have doubted it? What sorts of homogeneization is something so flimsy as “culture” able to hold back? This is the difference between a hula hoop and an iPhone. One is a product that may catch on or not. The other is an army that must be quartered.

The entire citizenry has revealed their vapidity. They are mere bodies stripped of all their limbs and plugged into a vast matrix of domination, perpetually vacated to serve as conduit for the flux of power. Lost creatures who fumble around in smug devices looking for love or distraction. They are children who have never learned to read maps or ask for directions, children whose intimate haunts that they never needed to impose on paper in order to navigate have now been thoroughly mapped by the devices they carry with them. The impoverished oral culture that remains has been forced through this new apparatus. There is no more face-to-face communication; all of it is legible now to the authorities.

The cellphone that shares my room sometimes like an evil stranger heralds the arrival of a new message with a cheerful arrangement of beeps. After a time I pick it up, already seeing the number of the one person I wish most to hear from. But there are only five digits on the screen. An automatic message from the phone company, wishing me a happy birthday—did I put down this day, of all days, as my birthday?—and offering me a present, a free gift, which I only have to claim by logging on to their website. I unplug the broken thing and, batteryless, it dies. Every device should be equally crippled. I turn back to the article I am writing.

In a parallel universe where justice reigns, all those cretins who claimed the internet would bring us closer together and Twitter would make the revolution are being lined up against the wall in an old park and shot. Not out of vindictiveness or vengeance. The purpose of the executions is educational.

“Don’t worry,” each of the condemned is told as blindfolds are affixed. “It’s all okay: we’ll update your Facebook.”

But parallel lines never intersect, and as ours progresses, the parks and squares empty out. Only wraiths pass by, absent to themselves, linked in a psychic death pact to another wraith staring somewhere at the same glowing screen. Only a few are still resentfully here, temporarily anchored by domesticated dogs for whom no application yet exists to take on walks. But even the housepets appear more neurotic as they pull against a leash that connects only to dead weight. They stare frantically at nothing, like inmates too long interned.

I think of a resolution to make on New Years. From now on, whenever I encounter a cyborg, I will speak only to the device, the brain, and ignore the flesh-head that still pretends to be in charge. Someone should start killing cyborgs, smashing the devices and liberating the golem they hold in thrall.

A year ago a wave of graffiti appeared in a park near my house. It was the first sign of life to have appeared there in some time. The occasion, I gathered, was the premature death of a member of a circle of young people who sometimes gathered on the stairs. “Alex,” the inked etchings inscribed, “We will remember you.” “Alex, brother, we won’t forget.” “Alex, you were my first love.” The wall stood almost always alone. The kids I associated with it appeared less and less often. Had I only dreamt them? The graffiti, as such, seemed like its own tribe. When the wall was washed clean, the writing appeared again, as if by magic. Now there is nothing there. I wonder if I am the only one who remembers that unknown boy. What has become of his friends?

And what superb instinct leads us to scratch away at the indelible façade of our world right at that moment when one of us snuffs out their meaningless life? As if the excess of agony standing like stale water that no apparatus yet designed can wash away pushes us Borf-like to attempt the impermissible, the inscription of our experiences in the metallic flanks of our prison. In moments like these it seems that everyone is aware that amnesia is included in the bylaws of Order; and therefore, to not forget, we must break the law. The only walls we are allowed to transform are on Facebook, mapping for the enemy.

Today, true grieving demands we resort to graffiti. In a time not far off—already arrived in some parts—it will demand terrorism.

Such a tragedy that suicide loses its enchantment with age. Precisely as we have nothing left to lose, we lose the resolve to go out with dignity in that ultimate, irrecuperable subversion. As though we were genetically programmed to weaken just in those years when we can claim empirical proof that, no, things will not get better, it seems the onset of a hormonal listlessness, the liquification of a certain moral fiber running through our core, enlists us to plod along with the whole of our society, look away or grimace as we might, but ever onwards, in furtherance of whatever harebrained course the species has set.

The political consequences of this resulting lack of elderly suicide bombers are immense. Social stability may lay thanks for its prosperity on the doorstep of that biological cowardice with which failures cling to failure and rebels, at their very best, cling to those same gestures that have long since failed them.

Even the engineers of each new apparatus are feeling lonely. How many start-up geeks marketing the latest Twitter spin-off or networking app sincerely believe that their invention might bring people closer? Convince a prisoner that freedom is made of walls, and they will build new cells all on their own. The guards have put down their guns but they can’t hand out bricks fast enough. The general population scouts out the new galleries and wings. Is this what we’ve been looking for?

We often tell of Baron Hausmann of Paris, the rightwing architect who redesigned the city just in time for the Commune, widening avenues and intersections, enclosing common spaces, to take the defensive advantage away from a population in revolt and allow an invading army easy access, changing the very terrain to favor a new kind of war.

We should speak more of Ildefons Cerdà, the utopian socialist architect who redesigned Barcelona in the 1860s. He sought to use architecture to bring about social justice and defuse class conflict by bringing rich and poor together in harmony. The modifications he left behind were nearly the same as those that had been imposed on Paris.

This is not new, but it is getting more common. Nowadays, hip CEOs debate whether technology will overcome alienation and powerlessness or whether civilization needs to be destroyed. One pole in this debate labors all the faster to develop new technologies, hoping to find the one that will really save us, and the other promotes conscious business and donates profits to NGOs.

Those who do not take sides in the social war and commit themselves to a path of negation maintain an affective allegiance to power, and the only way for them to reconcile this allegiance with whatever residual feelings of being human still trouble them in their new cyborg physiology is to decorate these allegiances, to pour even more affective attention into the “improvement” of the rites of power. The fact that what we are seeing is not an initiative of the traditional ruling class is evident in the selection of rites for decoration. Elections, military parades, leader cults, and similar processes are not the objects of adoration. In fact, the enthusiastic campaigns of civic improvement have tended to destabilize, delegitimize, or eclipse the rites that have traditionally been predominant in the sanctification of power. Neither have the initiatives come from the upper strata of the owning class; on the contrary, the most influential production to result in the decoration and intensification of the affective allegiances that tie people to power has been initiated by individuals from the computer-literate section of what would be defined as the working class, who in their astronomic ascent have founded companies that upset the preexisting capitalist hierarchy and now rank among the largest.

A large part of what economists might see as growth in the last few decades is an exponential explosion in the frenetically doomed activity of alienated people constructing new apparatuses to mediate alienation, with the unintended but inevitable consequence of spreading it to new heights and moments of life.

State planners and capitalists, while not the initiators of what has become an October 12, a Columbus-moment, in the field of social control, have responded in perfect form; the former by pursuing an aggressive institutional advance into the network of new and momentarily underregulated apparatuses that have been formed, and by integrating new technics into a revamped Cold War security apparatus; the latter by handing out bricks on low-interest loan, making sure that the supply never runs low and that no good deed goes unexploited.

Yet one has the feeling that they are not merely profiting off a plebian circus, that even the most powerful engineers are now moved by a quest to mediate alienation. As a historical rule, up until now it seems clear that no matter how universal alienation has been, the exercise of power acted as a drug to allow a certain class of people to find fulfillment in the midst of misery. This affective marker of the ruling class as distinct holders of power is what made Foucault’s theory of the immanence and diffusion of power an overstated argument and, if our present musings have set their teeth to marrow and not air, an argument that was ahead of its time.

Increasingly, a new measure of class (post-defeat class, as ladder and not as warfare) is how fully one can organize their lives in the space of the new virtual apparatuses.

Could it be that the charm of winning the class war has worn out? A power-holder must hold it against someone. Once the class war is won is the moment our prison guard realizes that he too is in a prison. He is no longer a heroic protagonist wielding his power against the savage masses, but a conduit through which power moves to maintain the good order of the apparatus. The emergency is past. Power no longer needs his creativity and dedication as protagonist to triumph. Put another way, power has risen out of the class of protagonists who heroically generated and organized it so as to organize itself at a higher level. Today, affective dedication and creativity are required of all those desolate souls who must inhabit a prison, regardless of their level of relative privilege.

The forerunner of this dynamic, now repeated at a greater intensity, is the patriarchal system of bribery that allowed any expendable proletarian or peasant man to play at being tyrant, and taste a small dose of the drug that made misery enjoyable.

Games of power-against played out at a continental scale color the early history of the State. Power-as-drug constituted an affective wage that roped people in to building State power. However, power-fiending protagonists do not always make decisions in the interests of stability or accumulation. The new apparatuses, organized on a logic of power-as-flux, mark a tighter arrangement whereby people are conduits of power and they pay to be played. They dedicate their affective energies to the improvement of their prison, independent of any wages, because to not do so would be spiritual suicide. While capitalism has always relied on unwaged labor, until now that labor has been provided by patriarchy or colonialism. In the Wikipedia age, the voluntary character of unwaged production is largely different.

The new apparatuses of social networking also begin to quantify informal power (the very informal power that has always held primary importance, even and especially in the institutions of formal power, which could not work without it) in “likes”, “friends”, and “followers”. But this version of informal power is not the kind created by protagonists, it is the kind produced by a mill wheel set spinning by a hundred chained bodies each chasing after their own loneliness.

There are some who attempt to pirate power at the level of property, using unregulated spaces in the new apparatuses to steal and share the digital commodities that make up such a large part of the global economy. But alienation extends so far beyond property, they can only hope to be privateers. The free circulation of the product they have liberated brings no benefit to the major concentrations of capital, whose spokespersons tell of tremendous economic losses. Surely, such crimes will not go unpunished, and in the future, prevented, as the State cannot abide unregulated space. But at a level much more dear to the world-machine than that of paltry capital accumulation, these would-be pirates are doing important work, thus they are allowed a certain license (though it is a license the most powerful nations will not recognize, just as the privateers were legally commissioned criminals in a polyarchic global system).

The service they render is to maintain and even expand the project of social control. They are the next chapter in the dilemma of the workers who occupy their factory and keep on producing. To name a common example, they have liberated music—what could be more beautiful? But this is not a pirate casette, taped off the radio and shared among friends on a boombox in the park. This is a digital file that will be added to an inhumanly extensive library, linked in to the web for the collection of metadata, and fed directly into the ears of the golem, who will continue to slide like oil over the surface of the muted landscape, blind and limbless, doing whatever it takes to avoid wondering how they got there.

Such music is the pinnacle of our civilization. What beautiful sounds we invent, to play while the ship sinks, the weight of its spite bringing the whole sea down with it.

A gust of tepid wind blows past me. I have finished my circle and found nothing to keep me. An alcoholic sits on a bench, howling at the empty streets. Young people drift by, ears plugged to the world, bobbing their heads to unheard tunes. A dog barks. A motorcycle idles. When someone passes close enough, I hear a faint, electric rendition of song.

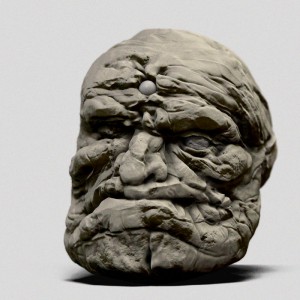

Where did that image come from? Trying to get ahold of the artist who did it.